In the early 17th century Cossacks in birch-bark boats travelled up the frozen rivers of Siberia in relentless pursuit of “soft gold” – the luxurious pelts of sable, fox, ermine, marten, beaver and squirrel which fuelled Russia’s economy. Along the rivers they constructed a series of wooden forts called Ostrogs, which were practical strongholds thrown up in weeks from the forest itself.

The Siberian fur trade was the primary engine of eastward expansion following the conquest of the Khanate of Sibir in the late 16th century. The taiga offered the thickest, softest pelts in the purest winter hues, making Siberian furs a staple export to European, Chinese, and Persian markets. At its 17th-century peak (roughly 1640–1680), state revenues from furs often reached 7–10% of total Muscovite income—exceeding 100,000 rubles annually in peak years—funding wars, administration, and later reforms under Peter the Great. Private trappers and merchants chased untapped stocks, but the tsarist government imposed a compulsory tribute called yasak on indigenous adult males (Buryats, Yakuts, Evenks, Tungus, and others). Drawing from earlier Tatar practices, yasak required fixed quotas—initially 10–12 sable pelts per man, later reduced to 3–5 as animals declined—paid in high-quality unfinished furs. Non-compliance triggered coercion: hostage-taking, raids, or abuse, with ostrogs serving as collection points, warehouses, and prisons.

This tribute mechanism made Ostrogs indispensable. Without fortified posts, tribute enforcement was impossible amid resistance, ambushes, or diversion by private traders. The Angara River became a key corridor linking the Yenisei basin to Lake Baikal and beyond. In 1630–31, Ataman Galkin founded Ilimsk; the following year Maxim Perfilyev built Bratsk to collect yasak from the Buryats. In 1661 Yakov Pokhabov raised Irkutsk at the Angara–Irkut confluence. Farther north, Pyotr Beketov established the Lena Ostrog that became Yakutsk in 1632. Each fort secured river junctions, housed small garrisons, and supported expeditions that reached the Pacific within decades.

The architecture of these ostrogs was rugged frontier engineering, relying entirely on local timber and skilled hand craftsmanship—no stone, no metal nails in most cases. The primary building material was Siberian larch (Larix sibirica), prized for its exceptional strength, density, and natural resistance to rot, insects, and moisture; it hardens over time and withstands extreme cold and wet conditions far better than most woods, making it ideal for foundations, lower walls, and exposed parts. Scots pine often supplemented it for upper sections or interiors, while Siberian cedar appeared occasionally for more prominent elements.

The carpenters used traditional Russian techniques with simple tools: axes, adzes, and chisels. The hallmark was dovetail notching, a strong interlocking joint where the ends of logs were cut into trapezoidal “tails” that locked tightly together without fasteners. This method created stable corners and joints, especially in towers and walls. Logs were usually hewn flat on two or four sides for a snug fit, and wooden pegs or dowels sometimes secured layers. The absence of iron nails reflected both material scarcity in remote areas and the effectiveness of the joints.

Walls came in two main styles. The earliest and simplest were vertical palisades: tall logs sharpened at the top and driven deep into the ground to form a stockade, typically 4–6 meters high. These could be erected quickly but were less durable long-term. By the mid-17th century, most important ostrogs adopted horizontal log construction. Logs were stacked in layers, with dovetail corners providing structural integrity and weather resistance. This technique produced thicker, warmer, and more defensible walls.

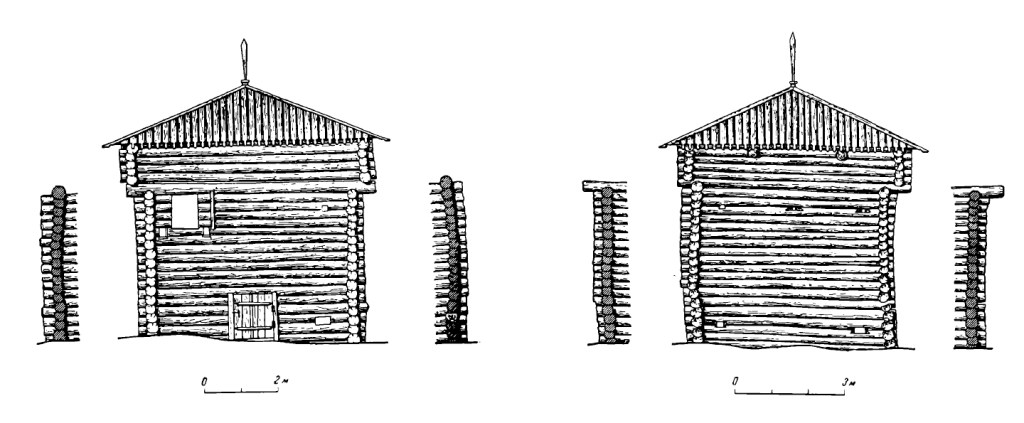

Towers are the most striking feature of Ostrog architecture: Usually square or rectangular, they rose two to four storeys and often featured overhanging upper levels. Roofs were steeply pitched and tent-shaped to shed heavy snow loads. The gate tower was typically the tallest and most elaborate. Overall, the architectural style was functional and military rather than decorative, drawing on northern Russian wooden building traditions but was stripped down for frontier needs with emphasis on height, mass, and defensibility over ornament. Little decoration appeared beyond occasional carved details on tower roofs or eaves. The result was an iconic silhouette—tall, angular wooden towers rising above log walls—that still defines surviving reconstructions.

The ostrogs gradually fell out of active military and administrative use between the late 17th to mid 19th centuries as Russia’s control of the region became secured and frontier role of the forts became redundant through the growth of secure permanent towns. Very survived into the 20th century and no complete Ostrog enclosure remains standing on its original site, though several towers have been salvaged and relocated and modern reconstructions have been built.

A notable example is the Bratsk Ostrog which was built by Russian Cossacks in 1631 on the Angara River in Eastern Siberia as a fortified outpost for the collection of yasak fur tribute. This comprised a rectangular enclosure (roughly 50–70 m per side) protected by a vertical palisade wall of sharpened logs 4–6 m high, reinforced in places with horizontal log framing. It had several square log towers (including gate and corner towers) and within the enclosure were barracks, storehouses, and probably a small chapel.

Under the direction of archaeologist A.V. Nikitin, the Angara Archaeological Expedition carried out salvage excavations of the site between 1957-58 ahead of its flooding by the construction of a reservoir. The work revealed remains of the palisade walls, foundations of several towers, hearths, pits and cellars and artefacts from its use. Two of the best-preserved towers were saved from flooding and following detailed recording they were disassembled and treated with preservatives. One was reassembled at the Kolomenskoye Museum of Wooden Architecture in Moscow and other is at the Angara Village Museum in Irkutsk region.

These log forts, built by intrepid frontiersmen, helped stitch together an empire that stretched from the Urals to the Bering Strait. The fur trade and yasak did not merely accompany Russian expansion—they propelled it. Ostrogs provided the fortified infrastructure to extract wealth systematically, turning frontier predation into sustained colonial revenue that underpinned Russia’s emergence as a continental power.

Leave a comment