At first glance, American death metal band Nile seems an unlikely case study for archaeologists. Their music is aggressive, fast, and deliberately overwhelming (we at Muddy.News can’t get enough); their album art is filled with gods, demons, and scenes of apocalyptic violence. Yet beneath the neck-breaking blast beats and growled vocals lies one of the most sustained and textually grounded engagements with ancient Egypt in modern music. Nile’s work offers a striking example of how archaeological knowledge can be translated (loudly and creatively) into contemporary cultural forms.

Formed in 1993, Nile quickly distinguished itself within extreme metal through its exclusive focus on ancient Egyptian history, religion, and mythology. Rather than using Egypt as an exotic backdrop or casual aesthetic, the band treats it as a primary subject, drawing directly on scholarly sources and reshaping them to fit the aesthetics and expectations of death metal

The band incorporates Middle Eastern-influenced scales, modal riffs, drones, and complex rhythmic patterns to differentiate their sound from standard Western metal forms. Ambient interludes featuring chants, percussion, and sustained tones create moments that resemble ritual space rather than conventional song structure. These passages often frame or interrupt the more aggressive sections, mimicking transitions between invocation and action.

Footnotes in Death Metal

At the core of Nile’s engagement with ancient Egypt lies an unusually serious relationship with archaeological and philological scholarship. Central to this approach is guitarist and lyricist Karl Sanders, whose long-standing interest in Egyptology extends well beyond casual reading. Nile’s lyrics are informed by translations of primary sources such as the Pyramid Texts, Coffin Texts, and the Book of the Dead, alongside secondary academic literature on Egyptian religion and cosmology and with frequent forays into Lovecraftian territory.

What sets Nile apart is not simply the use of these materials, but the band’s insistence on acknowledging them. Several albums include liner notes that cite specific translations and scholarly works, transforming CD booklets into something resembling abbreviated reading lists. The presence of bibliographic references in a death metal album is, at minimum, unexpected. It also signals a respect for academic authority that complicates assumptions about popular music as historically careless or purely fantastical. For some fans, album liner notes become a gateway to Egyptological reading; for others, the music simply reshapes how the ancient past feels—immediate, dangerous, and alive.

Deep Dive

Let us consider three examples of Nile songs to understand how the band resurrects archaeological texts through music.

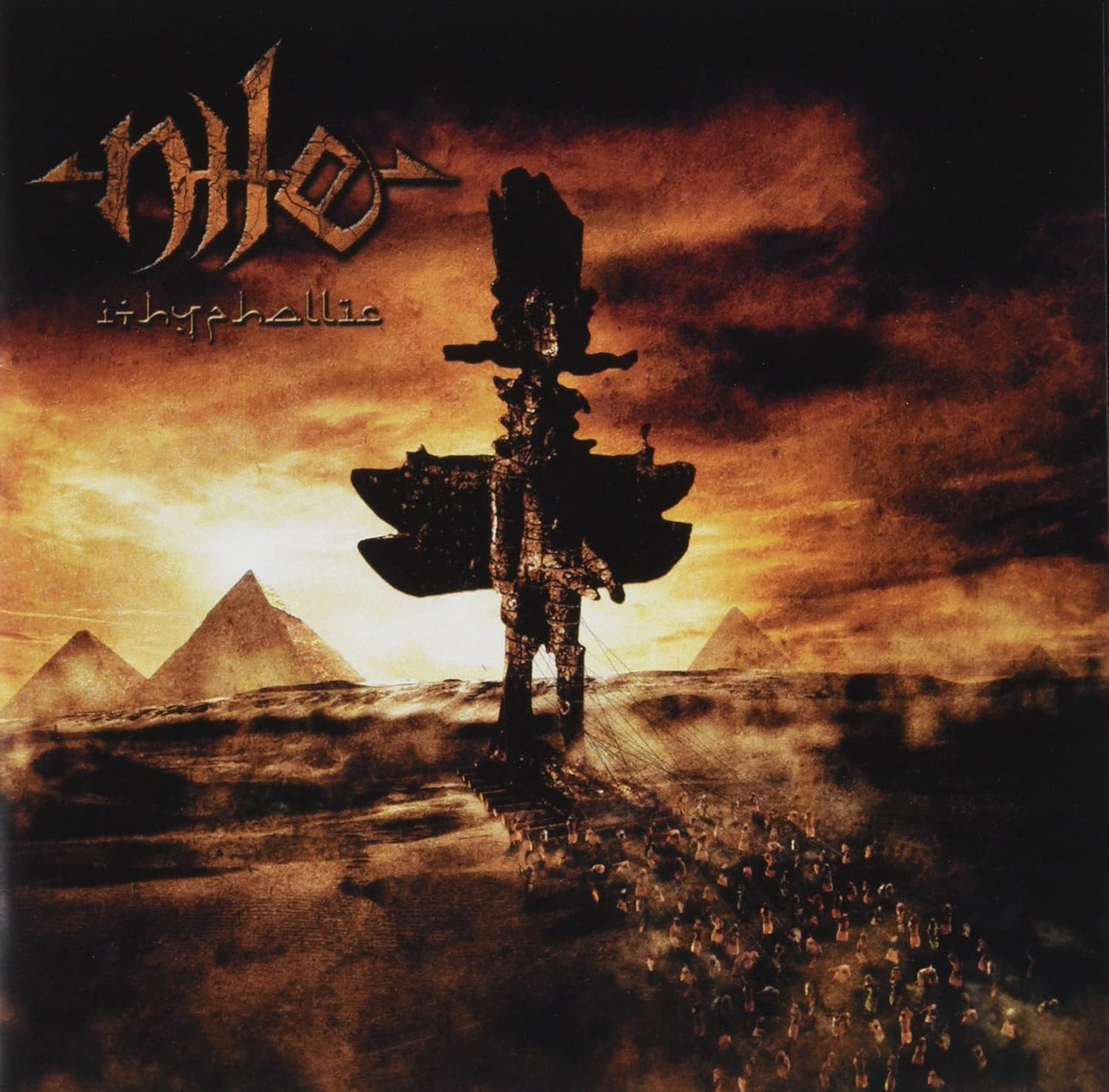

“Unas Slayer of the Gods“

This is widely considered Nile’s magnum opus and is arguably their most archaeologically dense track. The lyrics are based almost entirely on a specific set of inscriptions known as the Cannibal Hymn which part of the Pyramid Texts found in the tomb of Unas, the final Pharaoh of the 5th Dynasty (approx. 2300 BC). These are among the oldest known religious writings in the world.

The core of the song explores a specific segment of the texts in which Unas is depicted not just as a king, but as a terrifying entity who hunts and eats the gods to absorb their power and “heka” (magic). As described by the band in the album liner notes “According to these texts, Unas became great by eating the flesh of his mortal enemies and then slaying and devouring the gods themselves. Those gods that were old and worn out (Egyptian gods aged and died) were used as fuel for Unas’s fire. After devouring the gods and absorbing their spirits and powers, Unas journeys through the day and night sky to become the star Sabu, or Orion”

“Papyrus Containing the Spell to Preserve Its Possessor Against Attacks from He Who Is in the Water “

The lengthy title of this track is a literal translation of a rubric (a heading in red ink) found in protective scrolls like the Harris Magical Papyrus. Based specifically on Spell 31 of the Book of the Dead, the song explores the ancient Egyptian’s relationship with the crocodile (he who is in the water), the physical manifestation of sudden, violent death, sometimes represented by the demon-crocodile ‘Magah’ in magical texts.

The lyrics follow the structure of a Hekau (magical incantation), and call upon Amun to preserve the possessor of the spell from “lions of the wastes”, “the crocodiles which come forth from the river”, and “the bite of poisonous reptiles”.

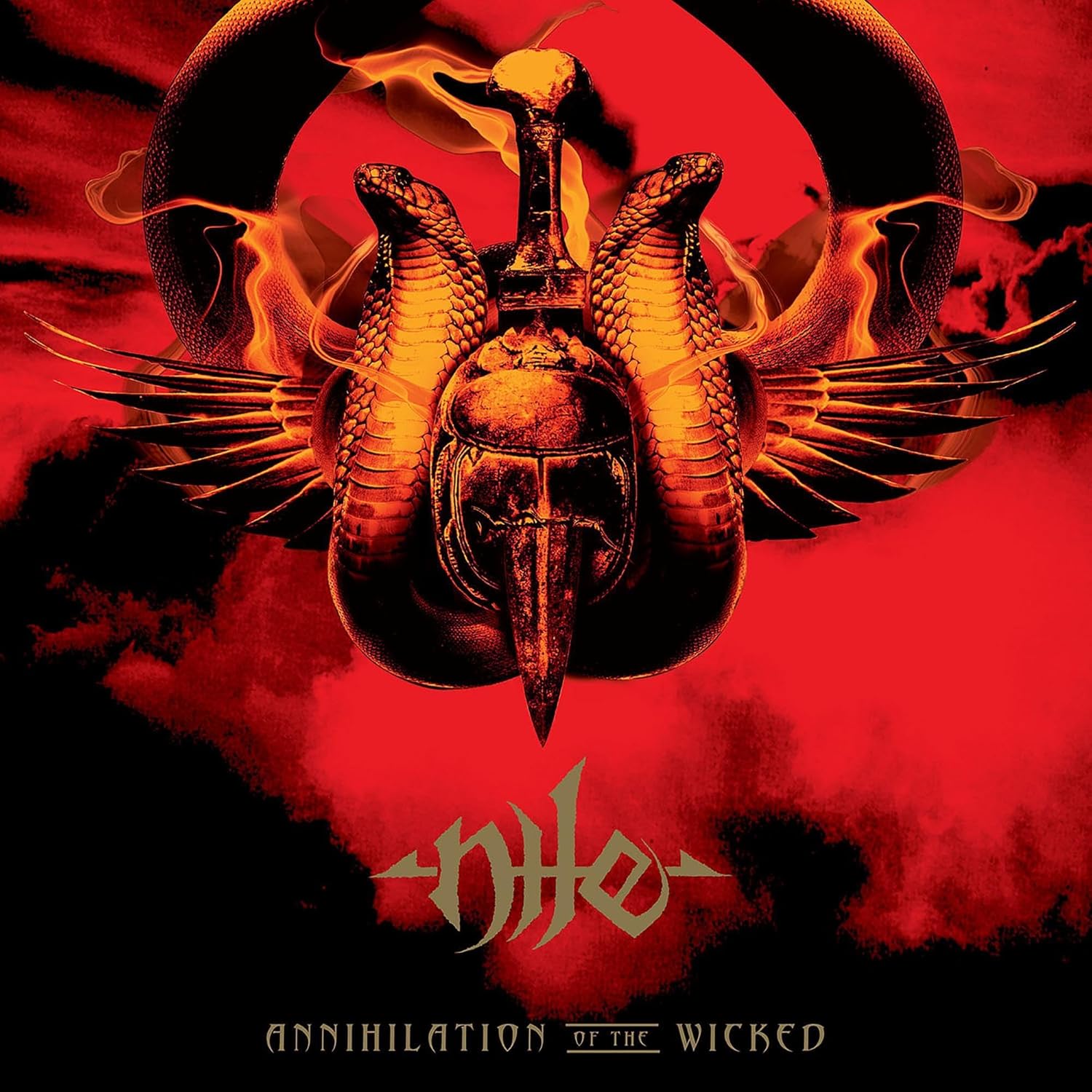

“Annihilation of the Wicked”

As described in the extensive liner notes, the lyrics combine Chapters 7 and 8 of the book “Am-Tuat” which describe the 4th and 5th hours of the night which harbour Seker’s kingdom. Seker may be one of the oldest of all the gods of the dead in Egypt and his dominions were supposedly situated in the ever-shifting sands around Memphis, and covered a vast expanse of territory. The domain of Seker was shrouded in thick darkness and unlike the places of the underworld wherein dwelled the blessed (where fertile plains and fields were fed by flowing streams of water), the place of Seker was formed of barren, endless desert wherein lived monster serpents of terrifying aspect.

Archaeology, Myth, and Metal Spectacle

Nile occupies a unique position in popular culture: a death metal band whose work is rooted in archaeological texts and academic respect, yet unapologetically theatrical. Their discography draws a balance between archaeology and mythology in which ancient Egyptian gods are treated active agents within a coherent worldview, aligning closely with how ancient texts themselves functioned, where myth was not separate from reality but embedded within it.

In a musical sense, death metal’s aesthetic and auditory excess, its fascination with violence, domination, and cosmic destruction, is well-suited to this material. Rather than distorting the ancient sources, the genre amplifies themes already present in them. The band shows that engagement with the ancient past need not be quiet, reverent, or confined to classrooms and museums, and reminds us that history, like metal was not always gentle.

Their latest release album includes the awesomely titled track “Chapter for Not Being Hung Upside Down on a Stake in the Underworld and Made to Eat Feces by the Four Apes“, showing the band have no intention of slowing down anytime soon.